In our efforts to “queer the tarot,” we might find the Rider Waite Smith imagery for the Ten of Cups overly heteronormative at first glance. A surface reading of the image might suggest that the pinnacle of emotional fulfillment is a life of heterosexual monogamy and 2.5 children. However, appearances can be deceiving. Hirokazu Kore-eda’s beautiful 2018 film Shoplifters (the original title translates to Shoplifting Family) showcases a family with a deep Ten of Cups bond. Despite their surface resemblance to a nuclear family, their bond might not have anything to do with biological family at all.

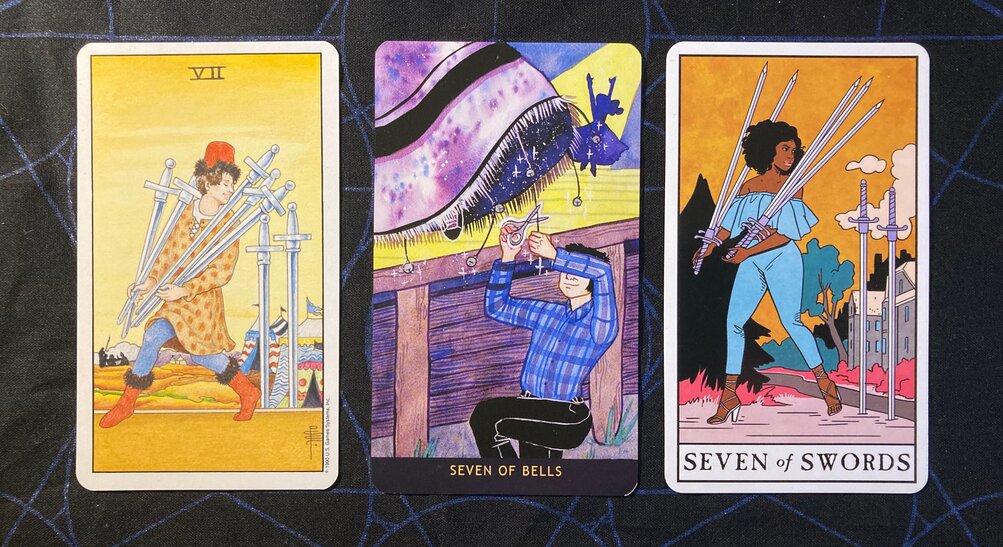

The titular “shoplifting family” engages in petty theft — shoplifting food and shampoo, engaging in small crimes of opportunity. We might tie this to the Seven of Swords, with its associations of sneakiness, deception, lying, and stealing. But, perhaps pushing against the expectations set by the title, we quickly find out that this is not some kind of criminal operation exploiting tiny thieves. The adults in this family all have “normal” jobs. Osamu works as a day laborer at a construction site. Nobuyo works at a laundry service. Aki works at a hostess club. Even the elderly Hatsue collects a government pension. So why steal shampoo?

Because it’s not enough. The family is constantly in the state of material deprivation the Five of Pentacles represents. They live in close quarters, skating by on the margins, making almost but not quite enough to survive without supplementing their earnings with ill-gotten goods. The film also deals with issues of employment precarity, warning that these jobs can be lost at a moment’s notice. Seen in this context, the shoplifting Seven of Swords makes perfect sense. When you’re living with so little, you do what you have to do to get by.

The inciting incident of the film comes when Osamu, walking home at night with the young Shota, sees a small child locked out on an apartment balcony. This is a position they have seen her in multiple times. She looks cold. She looks hungry. She looks sad. So they take her home and feed her dinner, serving up a mix of food that has been stolen and food that has been paid for. When they try to take her home, they overhear an argument that makes them reluctant to return her to a life of abuse and neglect. So she becomes part of their family. From the outside, it looks like kidnapping. Technically, it is. But watching the story unfold from their perspective, it feels like this little girl belongs with them. It feels right.

The family has the surface appearance of a nuclear biological family: father, mother, grandmother, children. But slowly through the course of the film, we come to realize that perhaps the little girl isn’t the only member of the family who lacks a biological connection to the others. We also come to realize that each of these people holds their own histories of trauma and sadness, that they are healing through the love they give to one another. Are they together because they are supposed to be, or because they want to be? What binds them? “Usually you can’t choose your parents,” comments Hatsue. “But then, maybe it’s stronger when you choose them yourself,” muses Nobuyo, “the bond.” Outside institutions and conventional understandings of family and morality can’t comprehend this alternative structure, very much found, very much chosen, and very much outside the law. I watched this film with a glow of happiness and an undercurrent of fear, certain that this could not last, desperately hoping it would.

At the midpoint of the film, the family spends a day at the beach. The image of five of them jumping above the surf (while Hatsue looks on off-camera, beaming with love and gratitude) is featured in some of the posters and other promotional materials for the film. This image is also a wonderful depiction of the Ten of Cups: a found family holding hands, playing in the waves, the ocean itself suggesting the deep emotions associated with the element of Water. Like any Ten, this is not the ending, the happy ever after. It is a moment in a cycle. I found myself wishing that the film could end with that scene, in that moment of pure joy. It didn’t. But sometimes the Ten of Cups is just one perfect day, wrapped in the love of your family, however it is you came to find one another, whatever it is you do to survive.