In honor of Halloween, I’m using the tarot to take a look at Hellraiser, written and directed by Clive Barker, with a terrific score by Christopher Young. The following will focus on the original Hellraiser film from 1987, with gestures towards the 1988 sequel, Hellbound: Hellraiser II, and Clive Barker’s novella, The Hellbound Heart. Spoilers for the first two films and the novella below!

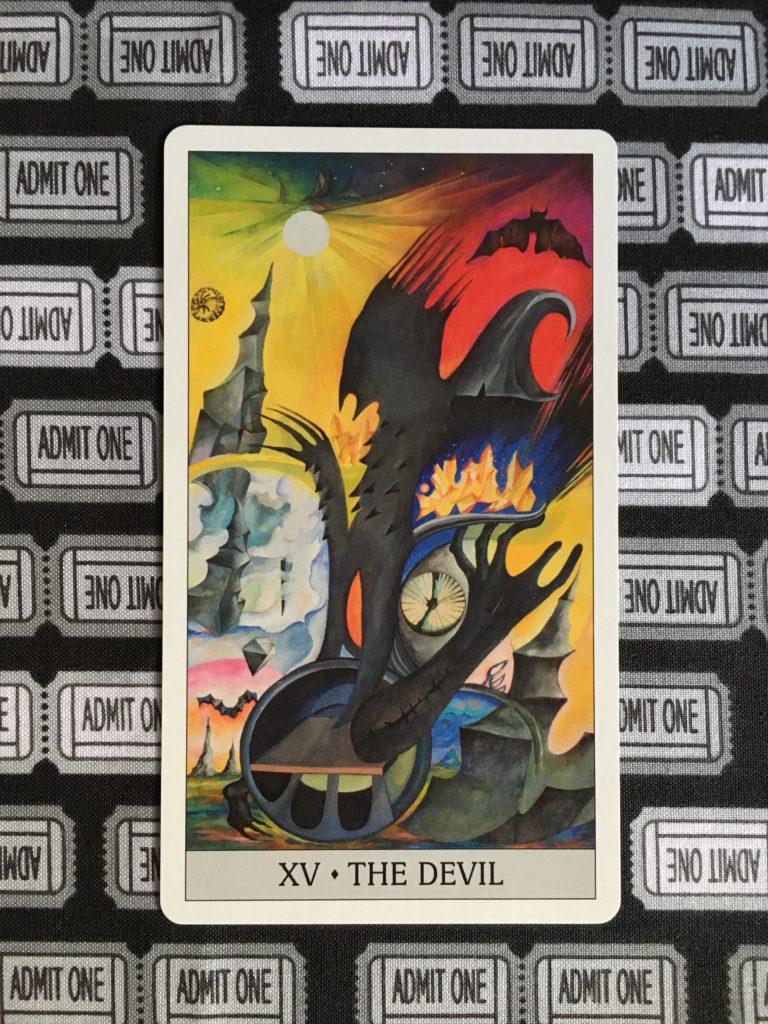

The trajectory of the Hellraiser mythos traces out a journey from the Devil through the Hanged Man and ending with the Hierophant, who takes charge of the cycle. In tarot, the Devil symbolizes obsession, addiction, pleasure, and sensual experience. We see this sensuality (which, to be clear, is not necessarily a bad thing!) in Frank and Julia. Frank seeks the Order of the Gash out of a drive to fulfill his insatiable lust. Despite his relentless pursuit of pleasure, Frank feels a bitter dissatisfaction. “It’s never enough,” he complains.

Julia, too, is ensnared by the Devil. Like Frank, she hungers for sexual fulfillment. In her case, the desire was awakened by Frank, and Julia associates her need with him. When he is partially resurrected, he is terrifying, but weak. Julia helps him out of a desperate desire, binding herself to him willingly. By the sequel, her lust has transcended Frank and she serves Leviathan, “The god of flesh, hunger, and desire.”

Seekers who crave otherworldly sensations may summon the Cenobites, “Explorers in the further regions of experience. Demons to some. Angels to others.” Their devotion to bodily experimentation is no simple hedonism, but a quest both demonic and holy. The Cenobites are summoned not only by the opening of the Lament Configuration, but by need. “It is not hands that call us,” Hell Priest says in Hellbound, “it is desire.” They come to those who seek to explore unfathomable realms of sensual experience, beyond the utmost boundaries of pain and pleasure.

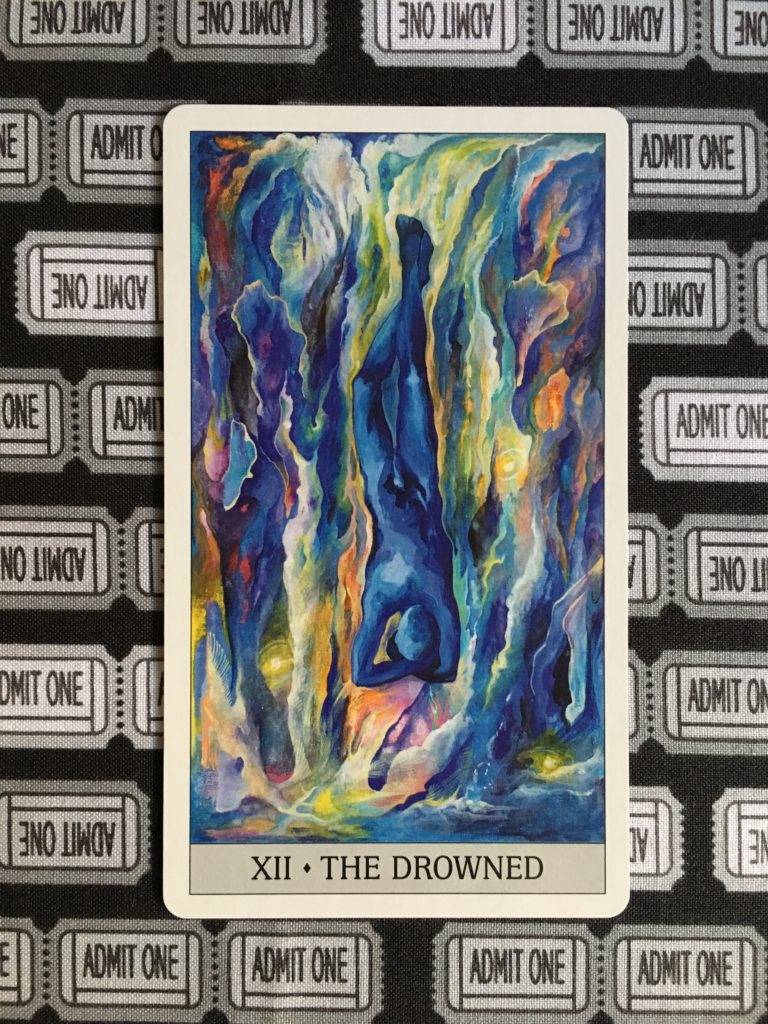

Once the Cenobites have been summoned, the seeker takes on the role of the Hanged Man, surrendering control to gain enlightenment. There are circumstances in which submission is a choice that can be rescinded at any moment. But there are also times when the choice to surrender cannot be taken back, and the Hanged Man must wait out the consequences. Once you’re on the roller coaster, you can’t jump out of your seat until it’s over. Once you’ve taken the psychedelics, you’re on the trip until the chemicals wear off. This happens on a supernatural level in Hellraiser.

The Cenobite designs may be modeled on fetish gear, but there are crucial differences between mortal BDSM practices and the rituals of the “Sadomasochists from Beyond the Grave,” even aside from the “Beyond the Grave” part. Once you submit to the Cenobites, you can’t take it back. It’s blanket consent that cannot be revoked. In the novella, the Cenobites have a full conversation with Frank, in which he confirms that he wants what they have to offer. He then immediately realizes that he has irrevocably locked himself onto this course, and he will have to ride the wave of sensory overload wherever it takes him. “I thought I’d gone to the limits,” Frank tells Julia in the film. “I hadn’t. The Cenobites gave me an experience beyond the limits. Pain and pleasure, indivisible.” The man for whom nothing was ever enough finds the meaning of “too much.”

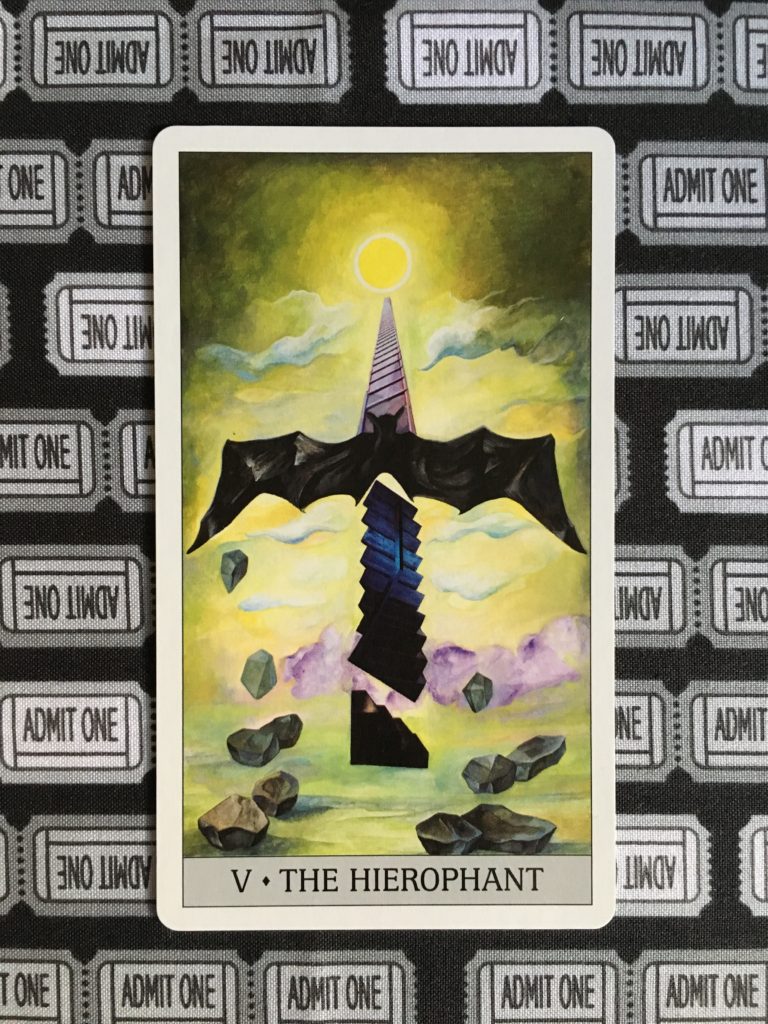

The Hierophant represents traditional knowledge, passed on by guardians holding the keys to wisdom. Once you have undergone the extremities of experience at the skilled hands of the Cenobites, you may become one yourself, a knowledgeable Hierophant perpetuating the cycle. In Hellbound: Hellraiser II, we find out that this is what happened to Hell Priest (or Pinhead as he is affectionately known). He was a mortal man who opened the Lament Configuration, went through the trials of the Cenobites, and then became, well, a Hell Priest. He is now the Hierophant, the one who has been to the outer realms of experience and back and knows the way. His role now is to initiate others into the mysteries of Hell.

Thus the cycle continues: a seeker who craves the sensual experience offered by the Devil opens the Lament Configuration, and the Cenobites are summoned by the combination of action and intention. The seeker then becomes the Hanged Man, surrendering to all the unimaginable torments and pleasures of Hell. Finally, the seeker may become a member of the Order of the Gash themselves, a wise Hierophant who will tear new souls apart in their turn.

I want to end with a character who comes close to the cycle but remains outside of it, at least in the first two films: Kirsty, who exemplifies Strength. Kirsty does not know what she is doing the first time she opens the Lament Configuration, and she insists that she does not want what the Cenobites offer. They are just as insistent that she come with them. Why? Perhaps it is simple sexism in the writing. Perhaps it is an attempt to play up the horror of the Cenobites and bring them closer to the slasher villains of the 80s (it’s worth noting that Frank’s extended conversation with the Cenobites in the novella is absent from the film). Perhaps there is some truth to what the Cenobites sense, and there is indeed a hunger within Kirsty — but she has control over herself, and she exerts control over them. Part of her could travel the path of the Cenobites, but she chooses not to submit. She faces Frank, Julia, and the Hierophants of Hell with an iron will. If she is ever to enter the cycle, it will be on her own terms.